Pottery made in Sarawak usually falls under two main categories. One of which is produced by the Chinese – generally descendants of immigrants from pottery-producing areas in Guangdong province about 200 years ago – through wheel throwing techniques involving creating pottery on a potter’s wheel.

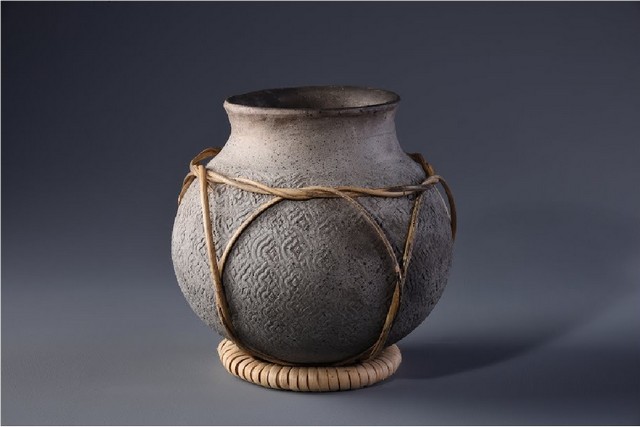

The other is the traditional hand-moulded, low-fired pottery made by indigenous potters, including the Ibans. Forms of this type of pottery tend to be small, round and utilitarian in nature, and are shaped by using the paddle and anvil method.

Adorning these potteries, which are also know as periuk tanah or periuk tupai,are motifs synonymous with the Iban culture. According to Universiti Malaya Museum of Asian Art, they include bunga kelawang, bunga luncung (with net design), bunga bunut, bunga mata and bunga terung.

Archaeological excavations and research, particularly in Niah Cave, suggest that traditional Iban pottery dates back to as far as the Neolithic Age, demonstrating not only Sarawak’s rich history but also the importance of ceramics as part of the Ibans’ way of life.

“Considering the facts that riverbanks, which provide high quality clay, typically surround Iban villages, the Ibans’ need for self-produced domestic ware and the necessity for pots in their daily lives, (this importance) seem to be rational.

“Hence forth, along with its daily use, for generations Ibans have used ceramics as a symbol of wealth and status, as fines for offences, as grave goods, for ceremonies and festivals, for burials, as domestic wares, gifts and so on,” writes academician and ceramics artist Funda Altin.

In the old days, Iban potters were mainly women, with men supporting their efforts through tasks such as making the required tools for the work, gathering materials, and preparing wood-fires needed to heat the clay vessels.

Today, given its rarity even in Sarawak, this indigenous craft is being famously practised and promoted by adiguru kraf or master craftsperson of Iban pottery Andah anak Lembang from Nanga Sumpa, a remote village located in the rainforest of Lubok Antu, Sri Aman.

Now in his 70s, Mr Andah learnt the art of pottery making from his grandmother and mother in his teenage years when he assisted them in producing pots for his family to cook and store food and water.

At that time, it was common for the people of Nanga Sumpa to make their own cookwares out of necessity; purchasing them would mean having the finances and travelling for many hours on foot from the village to the nearest town.

“However, it was not until I was much older and had worked offshore for a number of years that I decided to return to my longhouse and begin making the pottery myself,” said Mr Andah, as quoted by thesundaypost, adding that he was determined to keep the heritage of the traditional craft alive.

According to a number of interviews with the adiguru kraf, the decline of the craft in the village and Lubok Antu sped up with the completion of the Batang Ai Hydroelectric Powerplant in the mid-1980s that led to rapid development in the area.

The addition of a water route thanks the man-made lake in Batang Ai resulted in greater access to the mainland for villages including Nanga Sumpa, enabling more and more residents to buy plastic containers and metal wares in town – subsequently losing their preference for traditionally produced clay pots.

Furthermore, given the laborious production process of Iban pottery making, it seemed that the younger generation were in favour of opportunities some place else rather than continuing the craft.

“It’s not easy to make Iban pottery as it’s difficult work. The pots can easily break if you don’t know the proper technique,” said Mr Andah.

“That may be also one reason why the younger ones are not interested to continue making it.”

As one of the very few practitioners of the craft, Mr Andah has been very active in ensuring the longevity of the art of traditional Iban pottery making even before being awarded the title of adiguru kraf by the Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation (MHDC) in 2006.

He has been to various local and international expos to sell his potteries and showcase his craft at workshops and demonstrations. He has also been interviewed by local broadcasters to share his traditional knowledge and skills.

With the support of MHDC, he has been teaching the craft to the people of Nanga Sumpa as well as other local communities, students, associations, government agencies and private individuals as means to pass down its cultural values to the future generation.

Fortunately, preserving and continuing the heritage of Iban pottery is not a one-man show on Mr Andah’s part.

Last year (2020), the Academy of Sarawak Dayak Iban Association (Asadia), together with Sarawak Craft Council, started its very own Iban pottery making class in Kuching that was conducted by another Iban pottery craftsperson Nabilah Abdullah.

The association hoped that the craft can be mastered by the younger generation, who would then share their knowledge and skills with many others upon completion of their training.