In 1894, two enterprising individuals named K. Thamboosamy Pillai and Loke Yew installed an electric generator to operate their mines located in Rawang, Selangor.

20 years earlier, the first telegraph line was laid by the Department of Posts and Telegraph in Perak, connecting the British Resident at Perak House in Kuala Kangsar with the home of the Deputy British Resident in Taiping.

And 70 years prior, the first aqueduct made out of brick was constructed to transport water from the hills to the town of Penang, laying the foundation for piped water supply in Malaya.

These marked the beginning of the development of Malaysia’s utilities, which had since advanced in tune with the nation’s socio-economic progress throughout significant historical periods – from the British colonial era (as illustrated above) right up to its formation in 1963 and beyond.

The following are highlights of the evolution of electricity, water supply and telecommunications in the country:

Consolidation of Electricity Providers

By the 1900s, electricity development in Malaya was primarily driven by the rapid growth of the mining industry. In fact, the first power station in the peninsula was the Sempam Hydroelectric Power Station in Raub, Pahang, built by the Raub Australian Gold Mining Company in 1900.

Starting from 1904, these stations were constructed to supply towns located mostly in the west coast of Malaya with electricity, whether in forms of hydroelectric or thermal that burned energy sources such as coal, local wood and oil. In most cases, they were privately owned and operated, and were – by today’s standard – not large scale in nature.

In order to better meet the increasing demand for electricity, the British, upon its return following the end of World War II, established the Central Electricity Board of the Federation of Malaya (CEB), which began operation on 1 September 1949.

The board was a consolidation of the government’s electric utilities, and replaced the Electric Department, taking over three major projects considered by the department as measures to expand power production: the Connaught Bridge Power Station, the Cameron Highlands Hydroelectric Project and the development of a National Grid.

Most expansion projects under CEB focused on new thermal plants powered by the likes of diesel, oil and steam due the government’s lack of knowledge of the land, and social, economic and political instability that took place during the Malayan Emergency.

The board was also instrumental in the implementation of the first rural electrification scheme under the First Malayan Plan (1956-1960), where diesel generators were installed to provide lighting within New Villages (settlements for rural communities created by the government during the emergency to reduce their contact with communists).

Following the formation of Malaysia in 1963, at a time where electricity demand from tin mining dropped and usage for industrial and domestic purposes rose, there were four major players in electricity supply: CEB, Perak River Hydro-Electric Power Company (PRHEP), George Town City Council and Huttenbach Ltd, which supplied areas of Alor Setar, Sungai Petani, Kulim, Lunas, Padang Serai, Telok Anson, Langkap, Tampin and Kuala Pilah.

To combine these companies into one, CEB was renamed the National Electricity Board of the States of Malaya (NEB) or Lembaga Letrik Negara (LLN) in 1965.

For the next two decades, NEB acquired installations of the remaining public utility organisations in Peninsular Malaysia, having already done so with Huttenbach Ltd in 1964, followed by Penang Island Municipal Council in 1976 and PRHEP in 1982.

These acquisitions were essential in turning plans to establish the National Grid into reality, which had started in the 1960s with the central area network with Connaught Bridge Power Station in Klang being its precursor.

This network was then linked to the Sultan Yussuf Power Station in Cameron Highlands, extended afterwards to power stations in other parts of Peninsular Malaysia and eventually completed in the 1980s in Kota Bharu, Kelantan. Today, one of Malaysia’s primary electricity transmission networks is interconnected with electricity grids in Thailand and Singapore.

In 1990, as part of the Malaysian Government’s policy of privatisation, NEB was replaced by a ghovernment-owned private company named Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB).

At present, TNB is a major stakeholder of Sabah Electricity Sdn Bhd. Currently, the Sabah State Government is in the midst of reclaiming ownership of the state public utility company.

The Water Sector Reform

Up to the early 2000s, water supply services in Malaysia were under the purview of state governments, ranging from ownership of water infrastructures to operations or water services. In states such as Selangor and Johor, these services were privatised, meaning private concessionaires are accountable for the supply and treatment of water supply to consumers.

Despite the increasing demand for water supply due to the country’s swift socio-economic development at that point in time, the water sector was struggling to keep pace, with areas in the capital region on the verge of facing water shortages.

It was plagued by various challenges that could be divided into two fundamental issues:

- Inefficiency and ineffectiveness in terms of high levels of non-revenue water, low revenues, unsustainable tariff structures and weak state regulations; and

- Funding constraints, causing state governments to incur heavy debts and the federal government to find its financial resources shrinking.

As a result, water supply operators were unable to improve their water infrastructures and operations, subsequently failing to enhance their ability and performance in delivering quality services to consumers.

To tackle these challenges, the Federal Government embarked on a major water sector reform exercise in 2003, propelled by the formation of the first water supply-dedicated ministry, the Ministry of Energy, Water and Communications in 2004.

Following a series of feasibility studies by the Government as well as external consultants, a new model for the reform was created, on the basis of a shared responsibility between the federal and state governments regarding water management.

This led to amendments to the Ninth and Tenth Schedules of the Federal Constitutions approved by Parliament in 2005.

Specifically, amendment to the Ninth Schedule of the constitution involved the transfer of water supplies and services from the State List to the Concurrent List (refers to matters where both federal and state governments have powers to legislate).

Meanwhile, amendment to the Tenth Schedule meant revenue from water supplies and services that were previously under the purview of state governments were now shifted to the Federal Government.

Furthermore, two new legislations were approved in 2006: the Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Air Negara Act, 2006 and the Water Services Industry Act, 2006, which had been enforced since 1 February 2007 and 1 January 2008, respectively.

The former enabled the formation of Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Air Negara (SPAN), which today serves as the technical and economic regulatory body for the water supply and sewerage services in Peninsular Malaysia and Federal Territories of Putrajaya and Labuan.

SPAN regulates the water services industry in accordance with the latter legislation or WSIA, which provides licencing and legal frameworks for the regulation of the water and sewerage services industry in Malaysia.

Also part of the water sector restructuring was the establishment of Pengurusan Aset Air Berhad (PAAB), the holding company for the nation’s water assets. It is responsible in financing capital investment and developing water infrastructure.

Overall, these new policies as part of the water sector reform aim to, among others, establish a transparent and integrated structure for water supply and sewerage services; form a regulatory environment that facilitates financial self-sustainability amongst operators; and improve the quality of life and environment through effective and efficient water services management.

Since being enacted in 2008, several changes have been taking place, particularly participating states in Peninsular Malaysia and the Federal Territories (Sarawak and Sabah opted to be excluded from the reform).

These include the separation of responsibility between water operators (state governments) and the water asset owner (Federal Government through PAAB); corporatisation of state water supply authorities to improve efficiency; and setting of tariff based on uniform principles and procedures.

Analysts who have been monitoring the water sector reform note that the exercise, as it strives to achieve the aforementioned policy objectives, remains a work in progress. Nevertheless, the reform was able to establish good governance in the sector, consequently promoting more effective regulations, efficient operations and feasible financial mechanisms.

Telecommunications as a Basic Utility

Telecommunications technology in Malaysia has shifted time and time again. For everyday users for instance, after the telegraph, comes landline telephones and mobile devices afterwards, which themselves evolve as high-tech value-added services as well as 3G, 4G and even 5G networks are introduced.

As the country strives to progress economically and socially via the digital economy, Internet connectivity has become more important that ever, for without it, Malaysians may struggle to take advantage of the latest digital technology such as the Internet of things (IoT), big data and artificial intelligence.

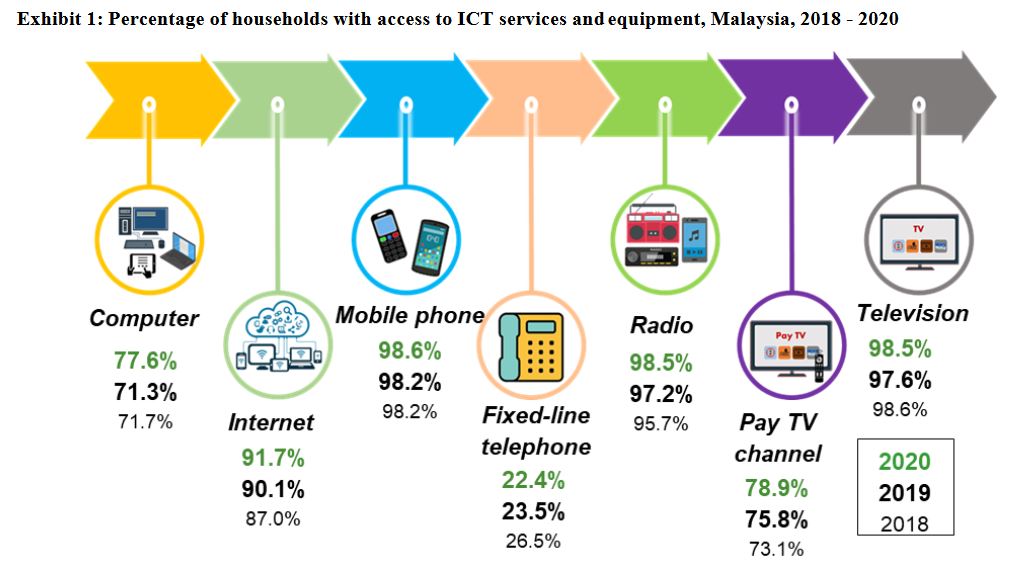

Yet up until 2020, in spite of the rise in households access to the Internet (91.7 per cent from 90.1 per cent in 2019, according to Department of Statistics, Malaysia), telecommunications was not viewed as a utility – not at least on the same level as electricity and water supply.

In December 2020, Penang became the first state in Malaysia to declare telecommunications as a basic utility when its state government made it compulsory for all developers of new buildings and development projects in the state to install fibre optic telecommunications infrastructure.

The enforcement is not only in line with the Federal Government’s Jalinan Digital Negara (JENDELA) plan as well as the state’s Vision 2030 aspirations, but also part of the Penang Connectivity Master Plan strategic planning.

By implementing this policy, the Penang State Government hoped to provide comprehensive high-speed broadband services to the people of Penang, and in turn stimulate the state’s digital economy sector at present and in the future.

Six months after Penang’s leap forward, the Federal Government classified telecommunications services as a public utility together with electricity and water supply.

With this, state governments nationwide were advised to refer to and utilise Garis Panduan Perancangan Infrastruktur Komunikasi (GPP-I) as part of their preparation of telecommunications infrastructure planning in existing development areas, new development as well as redevelopment.

They also should consider introducing specific policies that recognise telecommunications services as a public utility at the state level, as well as enforce telecommunications infrastructure installation requirements that are outlined in GPP-I, in line with provisions of the Uniform Building By-Laws, 1984 (UBBL).

This means that should state governments acknowledge telecommunications services as a public utility, new housing developments, for example, are expected to be Internet-ready before being occupied.

More importantly, telecommunications infrastructure expansion may also be more affordable, systematic and sustainable, contributing to a more proper local or urban development and landscape planning.

- Penang, Perlis and Sarawak have adopted both GPP-I and UBBL;

- Kedah, Kedah, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Johor and Kelantan have adopted UBBL, but not GPP-I;

- The Federal Territories and Sabah have yet to ratify UBBL but have accepted GPP-I; and

- Malacca, Pahang and Terengganu have accepted both, although they have yet to implement them at the state level.

References:

https://www.brinknews.com/water-supply-restructuring-in-malaysia-lessons-for-asia/

https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/MYS

https://www.tnb.com.my/about-tnb/historyhttps://www.thestar.com.my/tech/tech-news/2021/07/09/mcmc-telecommunications-recognised-as-public-utility-by-federal-government-three-states-on-board